Endre Kiss

Reconstruction of Nietzsche's Philosophy of Science

According to the genealogical approach, Marx, Hegel, and Nietzsche belong to the same community in a methodological, but also in an ideological sense. This common feature should come through in the most basic definitions of positivism as well. It's so because genealogy is the only and the very own historical view of the originally present-orientated positivism, of which original epistemological interest (Erkenntnisinteresse - after Jürgen Habermas) is anything but historical. Yet this flawless present-orientated epistemological approach might find objects (Gegenstand) of which existence is definitely historical, i.e. of which originally presentistic inquiry also entails such non-speculative historical starting points, i.e. in these cases within a correctly positivistic framework, the flawless present-orientated epistemology turns into a methodologically historical (diachronic) procedure as well, without changing its nature.

The idea of a Nietzschean way of re-shaping of philosophical sciences - actually as a summary of the epistemological consequences of Human, All Too Human - should always be interpreted in the closest sense. This very disciplinary consequence of critical positivism is the last phase of a philosophical-historical development process, which had started with the disintegration of Hegelian philosophy in the 50's and 60's of the 19th Century.

This Nietzschean re-organization, the real philosophical content of critical positivism, or - as Nietzsche quite appositely calls it in the title of the first chapter of Human, All Too Human - the reflection "Of first and last things" is the richest, most all-round, and most consequent philosophical innovation rooted in this great omnipotent philosophical cleavage of the mid 19th Century. In this context, Nietzsche's philosophy is the most important re-shaping of the post-Hegelian philosophical universe, accomplished in the extremely complicated fields of plausibility and possibility in the 1850's and 60's, and thus it's the most important universal philosophy of the new philosophical universe. It's a totally new philosophy not only because most of its positions are original, but mainly because it arises from a totally new philosophical situation which can be characterized by the new dilemmas of modern science, or the new conflicts of modern society - conflicts, which - mutatis mutandis - are still valid today in many respects.

Nietzsche was aware of all the challenges this "millenarian turn" meant (though the seeming lack of philosophical system in his aphoristic, but in fact "perspectivistic" philosophy had concealed this fact, with fatal consequences). Nevertheless, the new aspirations, a war of every philosophy against every other philosophy in the philosophical vacuum of the 50-60's, are quite different in quality from the mature form of Nietzsche's philosophy. Still it remains true that this philosophy can only be interpreted adequately in the original philosophical positions of the 50-60's. Against the words of Löwith: there's no real passage from Hegel to Nietzsche. After Hegel namely, there came no large passage to a concrete hegemonic future philosophy, but two whole decades of systematical vacuum, which utmost included the war of every philosophy against every other philosophy, and from which Nietzsche's philosophy truly arose. There appeared a qualitative difference for the new great philosophy first from the fact that Nietzsche had obviously brought the concept (Weltanschauung) of the "esthetic-philosophical-educational system" (Wilhelm Windelband) of classical German philosophy, and he absolutely stood for it as well, at least until his mature, middle period, which determined the generic, universal - or taking Nietzsche's expression - "ecumenical" character of his response to the new philosophical challenges.

However, the fact that Nietzsche had intensively dealt with all of the most important new philosophical streams of the 50-60's, plays an illuminating role as well. Beside the extremely and one-sidedly over-emphasized "Schopenhauer-effect", he "simultaneously" also reflects Lange's early neo-Kantianism (which doesn't have anything in common with the later) and Dühring's consequent and modern high-level positivism.

Thus the new philosophical concept is a vigorous new worldview prepared on the highest niveau possible; the philosopher (in his first period an extraordinary classical philologist by profession), bothered by a serious illness, has made a fundamental change in his career by Human, All Too Human, and - mostly because of the images and legends made up about him - no one would have imagined in his time, nor in the greater part of his "afterlife" that he had been able to establish such a genuine universal concept. Of course, about the turn of the 20th century, there were already a few people who had a clear insight of Nietzsche's real philosophical significance. Max Weber's relation to Nietzsche is still decisive today (regardless of the large secondary literature of the issue); Troeltsch never wrote any significant work about Nietzsche; George Simmel's great decisive Nietzsche-image even contains fundamental methodological elements of a 'philosophy of reality', however, it mobilizes not so much analytical revealing moments. Max Scheler consciously did not articulate the decisive challenge of Nietzsche's millenary positivism on him, and he developed Nietzsche's concepts further in a way followed by many other great thinkers later.

Practically, he saw in the Nietzsche of Human, All Too Human the very last stage of modern philosophy, or the final end of eternal validity (Gültigkeit). Ferdinand Tönnies had written a comprehensive work about Nietzsche, but his early and apparently unsharp philosophical interpretations don't yet reach up to the niveau of his own sociological works. Vaihinger's Nietzsche-concept includes some less important features among the significant ones, thus they lose a great deal of their striking force and coherence. However, it's mainly Vaihinger who realizes Nietzsche's pioneering criticist-scientistic directions almost congenially. Unfortunately, at the same time, he examines the 'political' and "sociological" aspects of Nietzsche's philosophy in an undifferentiated and unreflected way. His failures in the holistic reconstruction of Nietzsche's politics and sociology pull back his considerable achievements on the fields of the epistemological issues of science-criticism and positivism.

The qualitative step of Nietzsche's critical positivism means the new unification of positivism and criticism, which was of historical significance related to the philosophical streams of the 50-60's that had preceded or directly influenced it. Even the early Eugen Dühring was consciously aspiring for this, and Ernst Mach also put his critical positivistic aspirations in the seventies, but this, as "empirio-criticism" still hasn't gained his optimal reconstruction that would have demonstrated the specific characteristics of the Ernst Mach-founded unification of criticism and positivism. Another important and amazingly early (1876) experiment of Vaihinger elaborates the main philosophical processes after 1848. He finds in a very logical way that the eclectic tendencies that had lived in unity at Schopenhauer, dissolved later in their crucial distinct directions, though they kept developing parallel with one another, so it interprets Eduard von Hartmann as the developer of Schopenhauer's idealistic metaphysics, Friedrich Albert Lange as the developer of criticism which had also articulated at Schopenhauer, and Eugen Dühring as the follower and independent developer of Schopenhauer's rigorous positivism. Considering this, it's obvious that Vaihinger, who had seen (and stated) the most so far of the essential elements of Nietzsche's great epistemological concept, later simply converted to the selective and not well-informed, "feuilletonist" Nietzsche-interpretations of the nineties. Therefore, he was misguided mainly by false interpretations about the "immoralist" and the "prophetic" Nietzsche even after he made his own clearly outlined original ideas about the decisive new positivism of Nietzsche.

By making his paradigm of critical positivism, Nietzsche radically extended its methodological program as well. On the trace of moral evaluation, he made as an independent second step the universal historical identity of man an equal part of this philosophical sphere - in a way typical of the 50-60's programs in which the critical positivism and the universal identity are philosophical fields not in a discoursive subordination to one another. For it's not a genuine function of critical positivism to deal with the historical identity of mankind. It's not obliged to revaluate all values. Ernst Mach for example, had never directly formulated the revaluation of all values. The two huge new fields of really contemporary philosophy, the universe of 'critical positivism' and the universe of the 'historical identity of mankind' are not even at him in a (pre-critical) systematic relation with each other; they are in a discoursively non-subordinate relation with one another. Apart from this, Mach's Enlightenment and humanistic-reformistic view of society fits into the originally very broad issue of 'historical identity', i.e. in this sense, Mach's critical positivism absolutely doesn't lack the measure of revaluation either, even if it doesn't take the specific philosophical shape of Nietzsche's revaluation.

Therefore, the Nietzschean re-shaping of philosophical sciences includes firstly the immanently founded philosophical organon of critical positivism, and secondly, the non-subordinated, at the same level relevant new field that follows from the necessity of a re-shaping of all-human identity within these genuine new conditions of values and modernity. These issues mean the most important perspectives of his philosophy, and make it similar to an "open" system.

The reconstruction of the Nietzschean re-shaping of philosophical sciences has been made by a thorough examination of Human, All Too Human; by a reconstruction of the basic relations that outline in the Nietzschean variant of critical positivism. The distinct philosophical sciences appear spontaneously in a coherent structural relation at the reconstruction of the concept. These relations are therefore results of complex and detailed reconstruction, and starting points of further reconstruction as well.

Every single relation of the reconstruction connects two philosophical sciences in its elementary form. By "philosophical sciences" we mean basically scientific approaches, of which existence and relevance is explicated from the aspect of the new way of thinking (and which appears explicitly in Nietzsche's text). These sciences are "philosophical" because they appear as organic and legitimate perspectives of a theoretical new way of thinking, and also because several other sciences are also totally or partially modified by new 'philosophical', i.e. science-philosophical approaches (e.g. the sociology of knowledge).

These relations - each of which connects two diverse philosophical perspectives - have been organized strictly after Nietzsche's text. Then we allocated the fundamental relations reconstructed this way, to certain concrete philosophical sciences. Therefore, the relation of originally two 'philosophical sciences' has also become a 'philosophical science'.

We have thoroughly examined the parts of Human, All Too Human, which deal directly with the issue of epistemology. During the analysis of the text, we have separated the complexes that represent reality for epistemology. These complexes entered into clear relations with one another.

As a result, based on Human, All Too Human, the individual objective and epistemological moments have been arranged into three large independent complexes. First: cognition (present and past consciousness and practice), (past and present) reality-complexes (in the role of the most important objective spheres and aspects), and the complex of (past and/or present, historical and/or present-time) identity (all the universal genealogical topics that can't be directly grasped within the sphere of 'philosophical sciences' in the Weberian "value-free" [wertfrei] sense). In each case, we generalized these three great complexes by a strong analysis of the philosopher's (Nietzsche's) language itself.

The methodologically well-considered next step of our reconstruction - also strictly based on concrete sentences of Nietzsche's text - was the explication of the relations of the complexes to one another identified in the way introduced above. According to the terminology we have introduced so far, this has led to the identification of the distinct relations. To our surprise, each designated relation proved to be a well-known "philosophical" or theoretical science.

In this concrete context, we mean by "philosophical sciences" firstly every science referring real complexes of reality, and also philosophical approaches, which are interested in universal sense-giving.

Our first statement is therefore the most amazing isomorphia between the relations of the particular complexes and real existing philosophical sciences. In Nietzsche's epistemological texts, basic complexes have been organized into three groups of complexes which can't be identified with "philosophical sciences" in the above sense: (1) traditional philosophical sciences, (2) the most essential complexes of basic objectivity, fundamental complexes of philosophical evidence, and (3) the basic complexes of universal ecumenical and human sense-giving (foundation of historical identity).

The relations established this way (by a double reconstruction of Nietzsche's language) have also proved to be further philosophical and non-philosophical sciences. We called the new complex of the (philosophical and non-philosophical) sciences established this way the concept of the Nietzschean re-organization of sciences. As these sciences are based on a well-organized and consequent examination of real relations of real complexes, they make up the whole corpus of Nietzsche's critical positivism in a unique parallel which lacks external systematization and pre-decided immanent hierarchy.

The model of the re-shaping of Philosophical Sciences

Following the text of Human, All Too Human (as the alpha and omega of Nietzsche's philosophy of science), we separated the complexes within the three huge fundamentally different complex-dimensions of epistemological relevance (diverse topics [Gegenstände] of epistemological interests - sciences of epistemology of methodological relevance - philosophical disciplines of universal sense-giving/all-human identity). These three large complexes are the following:

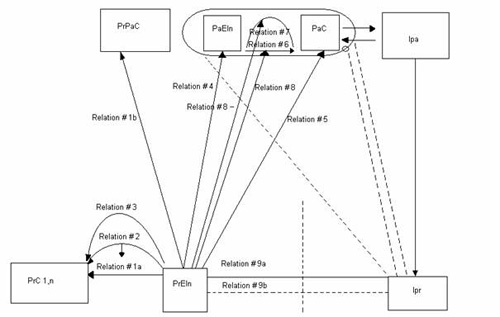

(See picture)

Abbreviations:

PrEIn = Present time (synchronic) epistemological inquiry

PaEIn = Epistemological inquiry in the past

CRTG = Complex (of real topics [Gegenstände]) in general

PrC = Present complex (of real topics) for synchronic epistemological inquiries

PaC = Past time complex (of real topics) for present time epistemological inquiries

PrPaC = Complex (of real topics) equally for the present and the past

Ipr = Universal sense-giving/all-human identity in and for the present

Ipa = Universal sense-giving/all-human identity in and for the past

The complexes of epistemological interests separated above (originally diverse topics [Gegenstände]) have been identifyed by our utmost close reading of the text of Human, All Too Human, a text very far from philosophical categorizations. After having reconstructed the basic attitudes of epistemological inquiry and the different complexes representing the universe of real topics [Gegenstände], it seemed to us, the next step must be the shaping of a matrix of these elements.

We established the following founding relations:

Relation #1 = PrEIn - PrC

Relation #1a = PrEIn - PrPaC

Relation #2 = PrEIn - Relation #1

Relation #3 = PrEIn - Relations #1 and 2

Relation #4 = PrEIn - PaEIn

Relation #5 = PrEIn - PaC

Relation #6 = PaEIn - PaC

Relation#7 = PaEIn - Relation #6

Relation #8 = PrEIn - Relations #6 and 7

Relation #9 = PrEIn - Ipr

Each relation between the basic epistemological attitudes and the most relevant complexes representing the universe of real topics, has proved to be equivalent with each of the following accepted philosophical or non-philosophical sciences:

Relation #1 = systematic epistemology of science, 'normal science'; furthermore:

Relation #1a = synchronic epistemology, with synchronic complexes of the present

Relation #1b = synchronic epistemology with a complex that exists in the present and the past as well (e.g. morals)

Relation #2 = critical and reflective philosophy of science

Relation #3 = hermeneutics, interpretation, sociology of knowledge (in a broader sense)

Relation #4 = positive-positivistic history of science

Relation #5 = positive history including the philosophy of history

Relation #6 = historical science (for our interpretation, evidently, history of science)

Relation#7 = historical interpretation, hermeneutics in the history

Relation #8 = the present interpretation of historical interpretation and of the historical sciences, sociology of knowledge (in a broader, historical sense)

Relation #9a = non-existing founding relation, non-existing discursivity (in the synchronic way identity comes from freedom, in the diachronic way it comes from historical representations)

Relation # 9b = positive interaction by enlightening and emancipatory practice.

A detailed analysis of each relation:

Relation #1:

We start out from the normal practice of epistemological inquiries. A systematic and synchronic epistemology is referred to topics [Gegenstände] of the present. This relation stands wholly within the universe and strategy of the positivistic epistemology and reflection of science. It is intersubjectively verifyable, and it has a clear-cut, professional scientific methodology. Both the existence and the importance of this relation are crucial for the Nietzschean re-shaping of philosophy. The great number of criticistic, hermeneutical, and other ways relativistic and relativizing concepts made Nietzsche appear to be - seemingly logically - anti-positivistic. Relation #1 is the most important evidence for the fact that all later nietzschean relativization of science relies upon a strong scientific basis1. Of course, the deeper analysis shows that like every basic epistemological relation, the positivistic practice of relation #1 is also based on interpretative conditions. But this doesn't mean interpretation would make the basic truth of positive epistemology, i.e. Relation #1 shoreless or blurry. This is right the really decisive issue for Nietzsche's whole interpretation and everyday philosophy. Relation #1 is substantially also an interpretation, but it's quite an extraordinary one. For it meets the basic positivistic and scientistic criterion of intersubjective verifyability, which is not a necessary characteristic of all kinds of interpretation. It's important that Nietzsche explains it explicitly as well, in Human, All Too Human: the general relativistic character of the epistemology of philosophical relevance simply means, that in every scientific statement, we have some false data. And since the same false data are constant in each concrete inquiry or concrete epistemological discourse, every scholar's work with the same "false" magnitudes. We are absolutely right to think, the results of these researches couldn't be perfectly strong. Therefore, critical positivism doesn't eliminate epistemological procedure; it doesn't send it to the dark night of borderless hermeneutics. Relation #1 is a fundamental part of the Nietzschean re-shaping of philosophical sciences. Therefore, in the nightmare of borderless interpretations, it's extremely important for Nietzsche to build scientific methodology into the whole concept of critical positivism. In his deep reflection, Nietzsche estimates scientific methodologies not just as instruments for concrete and singular scientific achievements and theories; he is absolutely aware that scientific methodologies themselves are quite as important triumphs of the scientific spirit as any other outstanding result (Nietzsche, 9/635). The same methodological consciousness prevails in Relation #1; Nietzsche decides consciously for a consensual interpretation of truth; he shapes with it his own scientific methodology on a high epistemological level.

This means not only a credo by methodological sciences, but a high-level strategic concept of philosophical work as well. For it's methods that found and sustain criteria of science against all-time metaphysics for example, and not individual (and ever-changing) scientific accomplishments. In other words, it's only methodological investigations, and not intuitions or visions, nor even current scientific results or theories that are capable of founding the semantics of philosophical language.

Today's Nietzsche-discussion is not so much sensitive for the obsessive anti-metaphysical velleities of the philosopher as we today might expect it to be. It rather tends to dissolve Nietzsche's after all radical positivistic concept in a much broader context of general philosophical interpretation, thereby transforming Nietzsche's originally positivistic concept into an anti-scientific one.

The difference between relation #1a and #1b consists not in the attitude or impetus of the methodological investigation, but in the real nature of the investigated topic (Gegenstand) as a complex of reality. Maybe the most important philosophical aspect of this is that relation #1b, i.e. the genealogy brings the historical dimension, the genuine historical nature of a topic (Gegenstand) into the seemingly exclusively presentistic (or synchronic) epistemological core of critical positivism2.

Therefore, the philosophical notion of truth by critical positivism is basically identical with the critical notion of truth by the critical interpretation of empiristic epistemology. This is the truth-concept Nietzsche shall later shape out and differentiate in many new directions.

Relation #1a

This relation brings presentistic (or synchronic) epistemology in connection with topics (Gegenstände) of genuine historical nature, i.e. of which existence includes at the same time a synchronic (presentistic) and a diachronic (historical) character by nature. We cannot speak about economics (politics, ethics, etc.) solely in a presentistic way. A present perspective of an investigation doesn't say anything of an economical topic (Gegenstand).

The difference is of philosophical importance. The judgement, which object the organized science of the age accepts as a topic (Gegenstand) of presentistic interests, is quite relative. After all, it's the social practice on the whole, that decides about it. Topics (Gegenstände) of clear presentistic sciences could be changed to topics (Gegenstände) of historical disciplines and reverse. For example, it considers the synchronic research of the weather the legitimate task of science, not the research of the "history of weather", although the weather is an object of which existence is undoubtedly historical3. The preliminary categorization (from the aspect of the specific nature of topics [Gegenstände] as real complexes), the heuristic acceptance or non-acceptance of - at the same time presentistic and historical - existence is of crucial importance for the essential innovation of the Nietzschean critical-positivistic re-shaping of philosophical sciences. For this categorization decides which object of research should belong to the synchronic and which to the diachronic sphere, and the legitimate 'philosophical' science of the latter is in fact genuine positivistic genealogy. Nietzsche himself also made genealogical researches and genealogical concepts (The Genealogy of Morals is his most known comprehensive work of this kind, and it's written with perfect methodological consciousness as well), and he was also interested in the latest positive results of positivistic genealogical researches and their increasing methodological issue.

Therefore, positivistic genealogy appears in connection of the re-shaping of philosophical sciences as relation #1a.

Relation #2

While relations #1 and 1a both establish the synchronic (presentistic) epistemological process, and the difference between them, as we have mentioned, comes after all only from our different interests of investigation (Erkenntnisinteresse - after Jürgen Habermas), at relation #2, the first reflective relation also appears. This relation refers to both relation #1 and 1a, yet it's sufficient for us to examine it only in respect of relation #1.

This relation also means a millenary turn of positivism - in the beginning inevitably absolutistic - into the direction of a controlled relativity i.e. the development of positivism into (a positivistic) criticism, i.e. it brings philosophical criticism into the new positivism. As we can see, the basic formula of critical positivism, positivistic criticism has already appeared by the assumption of relations #1 and 2, which has been sufficiently characterized by scientific methods and consciousness. Paradoxically, the Nietzschean statements about making positivism critical have only been used in argumentations, which tried to see against the spirit of Nietzsche's turn direct anti-positivistic moments in his new criticism of science, and therefore an essential anti-positivism in his whole philosophy.

We must emphasize that this specific relativization of positivism (in the sense of relation #1) is exactly the realization of Descartes' classical intonation of the "conceiving oneself to the search after truth" (like we find it in the first edition of Nietzsche's Human, All Too Human). At least we can realize this turn comes from the decision that the logic of science should apply the same criteria on itself, which were principally applied to its primary objects. This makes it evident that the relativizing turn of critical positivism is not irrational at all, nor anti-scientific, for the criteria of this differentiation can be identified and verified every time.

In the concrete Nietzschean re-shaping of philosophical sciences, the following - strictly scientific - moments of relativization appear:

- the relativity of our sense of space and time

- the genealogical relativity of the interpretations and results of positivistic history

- the criticism of the relativity of the fundaments of logic and mathematics

- the criticism of language

- relativity coming from broadly interpreted sociology of knowledge (Wissenssoziologie) and the connection between each system of theoretical objectivity

Relation #3

This is already the second reflective relation, and it refers to relation #2, and to #1 and #1a as well. This is the basic relation of the sociology of knowledge (Wissenssoziologie) in the broader sense; its language is yet hardly organized in this work of Nietzsche, but in its content it's an obviously novel initiative, which raises the thesis of critical positivism, which refers to the interpretation character of all reality to a high level. For it unifies the relations #1 and #2, and thus the interpretation character of reality can't eliminate the objectivities manifesting in them. It's presumably the most important, if not sensational innovation of Nietzsche's philosophy. His all-round philosophical, universal, and objective hermeneutics avoids the greatest danger of all kinds of philosophical generated hermeneutics, namely the elimination of the sphere of objectivity and therefore the legitimation of scientific character. This hermeneutics therefore doesn't abolish the validity (Gültigkeit) of relations #1 and #2. The anti-anthropomorphic tendency, which had been strongly articulated and raised on a general philosophical level by the young Dionysian Nietzsche already, obviously comes to its full in this relation, for relation #3 is also the unmasking of the philosophical anthropomorphization, which is inescapable for unreflected thinking. This hermeneutical reflection of this new relativistic positivism (Relation #3) didn't conclude in a restoration of any anthropomorphic velleities.

Relation #4

This relation is the reference of the present cognition to the former one. Nietzsche had always been interested in the history of science, for it had constantly been providing positive material for his unquenchable interest in the detailed description and invoking reconstruction of real historical processes. In principle, critical positivism obviously requires an endless number of items of positive knowledge for raising genealogical trains of thought. Therefore, relation #4 includes firstly the positive factual material of the history of science, but secondly - and this also follows from the existence of relation #2 and #3 - it examines concepts of the history of science also from the aspect of values, which is one of the most important sources of the sociology of knowledge in a broader sense. So it's better to describe the positive science-historical relation of critical positivism as "critical history of science".

Relation #5

This relation connects present cognition with past reality-complexes. It is of no particular philosophical significance, but that doesn't mean this relation or the general philosophy of history attached to it doesn't have its own place and values among the newly re-shaped philosophical sciences. It is naturally related to relation #1a, provided that relation #5 has no genealogical reflection of its own.

Relation #6

This relation connects past cognition with its past object. This relation has no direct importance in the Nietzschean re-shaping of philosophical sciences, for it is totally a relation of the past, therefore it gets in connection with the center of critical positivism only in the aspects referred specifically to it. By these references, it occupies its quite important place in this system of sciences.

Relation #7

This relation reflects upon the past (historical) cognition of past (historical) reality-complexes. Nietzsche shapes genuine and original recognitions concerning this relation, which should be explored in detail by Nietzsche-research. He uses a great amount of material belonging to this relation in his work. At least, he develops with relation #7 a specific new philosophical science too, a peculiar historical sociology of knowledge. This new science unifies two aspects: firstly, it's primarily an ordinary historical approach, but secondly, the object of that historical discipline is a clear-cut sociology of knowledge, practiced in a concrete historical era.

Relation #8

Present cognition already generally refers to former leading theories of science - mostly to the surprisingly broad and extended concepts of critical positivism. In its broader context, Nietzsche's relation to Hume (very much like Kant's relation to Hume) emblematically shows Nietzsche's all-sided consciousness in the elaboration of the antecedents of critical empirism.

Relation #9

This relation includes relations #9a and #9b.

Relation #9a strongly demonstrates the antagonistic difference and the deficiency of desired direct dependence between the critical positivism in the narrow sense, and the identity-centered approach, also in the narrow sense. This is one of the deepest insights and masterpieces of Nietzsche's philosophy. This insight consequently prescribes the division of the progressive new philosophy definitely into two great parts. It means, modern critical empirism consists firstly of a fulfilled empirical criticism, and secondly of an epistemologically not fully determined philosophical center about identity-questions. The critical situation following from this shortage of full epistemological legitimation can be solved through the outcome of human freedom and ecumenical human tradition (like Dyonisos).

Relation #9b can be realized in a historically successive manner, as a result of enlightening and at the same time enlightened practice. As the identity of the present (Ipr) was not built upon the cognition of the present (PrEIn), but on the traditional and ecumenical contents of historical cognition, at the present time there is no optimal transition between Ipr and PrEIn. From a systematic view, relation #9 is one of the key parts of Nietzsche's philosophical concept. It demonstrates that - as we have seen - the issue of (historical) identity cannot be brought in discursive, systematic connection with critical positivism, not even with its philosophical summary. This is the point where the philosopher's free revaluating activity begins.

We can say, this new structure, this co-ordinating conjunction in the center of Nietzsche's philosophy as a whole, namely the two centers, which can't be brought into any discursive relationship with one another, are the structurally deepest results of our philosophical reconstruction.

Yet it's obvious that not even the most accurate definitions of these two centers could be sufficient for grounding one of the next most important task of philosophy, i.e. theory-making. Critical empiricism pursued to its end doesn't result in a theory. The philosophical construction of identity (exactly in the former, Nietzschean sense) although resembles a theory, yet it must not be mistaken for a peculiar theory-making of critical empiricism itself. By this we also stated that - against all appearances - the center of critical empiricism and that of identity are not identical with the original relationship between fact and theory, or that of science and theory. There is a proper way leading towards the theory-making, even from the positivistic, critical empiricism, and also from Nietzsche's own epochal criticism.

The outlines of a philosophical genealogy made up by the numerous positivistic historical relations of Nietzsche's reconstructed relations of philosophical sciences is an important stage of this way. This philosophical genealogy as a whole, unifies the relations of the historical character of a positivistic type. In its historical age, it was rather fighting against speculative historicism, than against presentistic, anti-historical criticism. Nietzsche's philosophy, being so rich in perspectives, avoids the classical antagonisms between synchronic-diachronic and presentistic-historicistic approaches. The simple reason why it is capable of this lies in the fact that the Nietzschean totality of this model of relations is capable of unifying definitely presentistic and definitely historical, synchronic relations into one system.

It's also obvious that this reflection on a new philosophical genealogy was quite suitable for founding the problem of theory-making, which was- and is not involved in the central duality of the philosophical empirism of Nietzsche (in the co-ordinating conjunction of a criticistic empirism and a philosophy of historical, ecumenical identity). The atomic empirical verifications of the presentistic view were capable of creating causal chains, upon which later a unique positivistic theory-making could be built. Positivistic genealogy is a unique semi- or quasi-theory; it is an inescapable stage of legitimate positivistic theory-making.

According to this view on genealogy, Marx, Hegel, and Nietzsche belong to the same philosophical club. This common feature should come through in the definitions of positivism as well. We must make sure that for a great part, Hegel - like Marx - should be interpreted as a positivist, too.

For example, when Marx sets 'material production' as an object of research in Grundrisse, he is right. His object is the material production, his approach is obviously synchronic, not diachronic. But his presentistic oriented research has inevitably changed into genealogy at one point, because material production is obviously an object of which existence is typically of a historical kind. That's the way on which clear-cut presentistic epistemology should become genealogy and consequently assimilate synchronic qualities. We see, this process comes absolutely not from a decision of the researcher, but it's a consequence of the sphere of the objects of his studies.

Later in Grundrisse too, at a point of the presentistic analysis of basic terms, Marx discovered a possible Hegelian way to proceed. But he did deliberately not choose this way (Engels apparently didn't follow him in The Dialectics of Nature), but he chose exactly the positivistic genealogical way we have just reconstructed at Nietzsche, instead of a Hegelian revival of his philosophical fellow.

It's another question that Nietzsche's re-shaping of philosophical sciences is right an emblematic evidence for the fact that critical positivism (and the revolutionary turn that had provided a basis for it, i.e. that the verification status of the most important sciences was complete) made a huge turn for the future development of sciences (or in the legitimation of philosophical semantics based on that) and philosophical ontology. Critical science did not directly verify materialistic ontology any more, which doesn't mean that it had verified any other kind of ontology. This at least gives an explanation for Engels' distorted Hegelianism, and it makes its contrast to Marx's straight stand by the positivistic genealogy labelled by Nietzsche even more visible.

(A case study to represent Nietzschean positivistic theory-making, or how Nietzsche should have given his own theoretical interpretation of Hitlerian fascism?). The researches on fascism had an immense swing after 1945 not only from a historical, political, or history-philosophical aspect, but they might as well provide us consequences relevant for the philosophy and logic of science.

With the direct and brutally self-evident determinations of the framework of its interpretation, and with the transition of descriptive aspects into evaluating ones on the level of real objective interconnections, fascism has created a unique field for the philosophy of science. But, as we are trying to argue, fascism doesn't create a unique science-philosophical situation from this aspect only.

From the aspect of socio-theoretical theory making, one of the most important characteristics of the issue of fascism is that it has been researched the most thoroughly by every approach of science that had any interest for it in the past half of the century. It's impossible for any future system of society to be examined so thoroughly by history. It's totally unimaginable for any other society to have a monographic work written exclusively about the mysteries of its propaganda machinery. It's not only the extreme social destructivity of fascism, and the extremely well-founded elaboration of its system of society that provides extraordinary conditions for the logic of science, but the extraordinary and extreme theoretical complexity of its phenomenon as well.

The unique character of the logical side of the analysis of fascism is clearly shown in the fact that a multitude of interpretations are claiming the exclusive right for the interpretation of this social structure for themselves. So there is a social structure on one side, about which more historical facts have been revealed by historical research than any other eras in history so far. On the other side, contrary to these self-evident connections, there is a multitude of interpretations, which have gained general acknowledgement as the meta-science of the interpretation of fascism, or "fascism-theories" - as it is featured in literature. Taking the classification of an important piece, in such a piece of fascism-theories, six basic ways of interpretation are distinguished - explanatory theories based upon the theses of "totalitarianism", "Soviet-Marxism", "the primary role of politics", the "alliance with the capital", the "genesis of middle-class", and the "fulfillment of middle class" - which latter one got realized during the mature stage of fascism.

So what justifies the fact that a social reality, which appears as totally self-evident for everyday consciousness and for moral and mental common sense (an "absolute zero" in an ethical and history-philosophical sense) is still being interpreted by so many types of interpretation, each of which exclude one another?

The fact that the logical and heuristical problem we put above is still topical is sufficiently demonstrated by the "historians' quarrel" (Historikerstreit) that took place in the 80's West-Germany, which tried to instrumentalize even some theoretically legitimated fascism-theorems for his shocking attack of a holistic rehabilitation of the universal phenomenon of fascism.

Many theoreticians have put methodological and meta-theoretical reflections they had acquired as working experience. For example, Richard Saage emphasizes a phenomenon in the struggles of rival theories, as their authors interpret their own "particular" aspects as the total phenomenon of fascism. The science-philosophical issue that gets articulated in the research of fascism, appears spectacularly at this point. The "theories" (the six great types of theories featured in our example) are in a mutual and circular struggle with one another. The truth content of each "theory" itself cannot be doubted. Therefore, the distinct "theories" can't be united into one great total theory, although the empirical matter and the interpretation that provide the basis of each theory wouldn't exclude one another.

Each interpretation of fascism in this circle is legitimated (not taking a few curious exceptions). They all put relevant issues in the center. These concrete issues of the interpretation of fascism lead to "socio-philosophical", and in another context, to "positivistic" theory-making.

A summarization of scientific and theoretical cognition is the most important starting point from the aspect of the logic of inquiry. It's not a coincidence that this moment already exists even in the spontaneous forms of common language. All analyses of fascism have been called "theories" for decades even if the explanations were not really "theoretical". So the term "fascism theory" has gained general acknowledgement in the research of fascism before any examination of the real status of the analyses. The spontaneous mutation of the ordinary language of science provides this issue of the philosophy of science with linguistic terms. It can be easily pointed out that although the definitions of "science" and "theory" are unexpectedly close to each other, they can still remain very unclear, and shockingly problematic as well.

In the case of fascism (but this can go for the theory-making processes of other social sciences as well), it's not that a kind of existing theory (of society) should be applied for the phenomenon of fascism. Instead, the main point is to constitute a definition of fascism in a scientific manner, with special regard to the real-causal respects of its peculiar qualities. But by this decision, the originally scientific, the real-causal (and at the same time genealogical), and the theoretical constitution in a narrow sense became identical. The seemingly eternal duality of theory and reference melt down in this common unification process.

In the case of fascism, the practice of the normal scientific procedure essentially overlaps the work of the theoretical reconstruction. As the facts necessary for (also) the scientific reconstruction of fascism cannot be reconstructed twice during the same act, the distinct theories cannot be compatible, not even if the positive results of each reconstruction could be made compatible with each other. It's impossible to get two different results of the reconstruction. So one of the final results is the exclusion of another possible final result (of another concrete reconstruction). The thesis of "fascism, as the hegemony of monopol-capitalism" excludes the thesis "fascism, as a variant of Bonapartistic political order". The first thesis, when raised to a distinguished theoretical position, puts a final suggestion for answering the question why fascism as a political order had actually won regardless of the truth of many other legitimated reconstructions.

The incompatibility of distinct theories, and at the same time, the constitutive isomorphia of scientific and theoretical reconstruction find their final explanation in the unique issue of fascism. It's so because the basic issue of fascism does always include a decisive real-causal moment. The issue of fascism always includes the real-causal moment of its own evolving and victory. Consequently, at least it's the interpretation of the real reason of the political victory itself, which makes the decisive difference among the great number of competing interpretations. It demonstrates how a really concrete real social or political issue can appear on the "scientific", as well as on the "theoretical" level as a reason for the proceeding of a process. The real cause becomes in its original status the concrete interpretation itself.

Therefore, the researches of the phenomenon of fascism are not aimed at the "explanatory" description of the phenomenon, but description and 'explanation' are aimed at a concrete genealogical and real-causal issue, i.e. the real cause of its concrete victory as a historical fact. In this direct real-causal orientation do their "scientific" and "theoretical" explanations become identical. This is the point where the concrete competing explanations become incompatible with one another, because each theory gives its own solution exactly by pointing out the main cause of the victory of fascism. It's clear that each theory differs from every other theory in this point. It shows what it means when the real cause becomes identical with a theory of a whole.

The suggestions for causality thus evolved as the results of interpretation, unite scientific and theoretical elements in themselves. They are positively scientific in their concrete contents (for example, the concept of the "alliance" between the capital and fascist movements, or the Führer-theory, etc. hint at a quite obviously material moment which can be reformulated by means of sociology). But there appears an unexceedable theoretical moment in the act in which an explanation chooses a certain 'scientific' moment to be the theoretical concept of real-causal suggestion.

The neo-Kantian question of the young Lukács was like this: "There are pieces of art, but how are they possible?" A variant of this question goes on like this, in our present context: "There are fascism-theories, but is one theory of fascism possible?"

A theory of fascism is possible if its interpretation can reconstruct the real causality that gets realized in it as an all-round explanation, to make the theoretical essences of other possible real causalities subordinate to it. The real causality that gets into a theoretical position doesn't possess any speculatively, systematically, or pre-theoretically exclusive role. The One concrete real causality possible for The One Theory of Fascism (e.g. "the German way") is therefore not to be preferred to other variants of real causality in the objective, scientific sphere. On the objective level, the individual spheres of real causality don't necessarily get in touch with one another. For example, the thesis of the separation of political executive power says nothing about the behavior of capital in history.

Therefore, The One Theory of Fascism, i.e. the reconstruction of the total phenomenon of fascism is possible on a theoretical level if a concrete interpretation, which gets its coherence from the scientific (not the theoretic) sphere, can give a plausible explanation for the phenomenon of fascism (in fact, for its taking over of power). Its real plausibility consists in its ability of legitimated refutation and therefore elimination of all the other concrete real causalities from the interpretation of fascism. The victorious theory must not eliminate the different empirical contents of the other theories (for a scientific real causality has no permission to exterminate another scientific and empirically legitimated real causality). It must eliminate other theories by the pointing out of its own option for the interpreting real cause as a theory against the options of other theories by their pointing out of other options for the interpreting real cause as a theory. Therefore, the incompatible theses don't exclude one another on a scientific level, but they actually do on a theoretical level!

The special feature of the result we have just demonstrated is made up by the fact that among scientifically equal, legitimately reconstructed real causalities, one shall get into a central, actually theoretical position. Therefore, the measure that qualifies the scientifically real causal options is pragmatic and genealogical at the same time, which is not an unexpected or impossible outcome after all, from the aspect of "cognitive interest". So the components of empirically supported scientific reconstruction, and genealogical-causal reconstruction are getting mixed together within one unit.

It's quite remarkable that the concrete real causality as a "theoretical" position doesn't undergo any changes during this change of status. Therefore, acquiring newly a theoretical position is not accompanied by changes in the original definitions in the scientific dimension.

The thesis of the real causality as a theoretical interpretation is radically different from the views according to which theoretical theses are some kind of "generalizations" of diverse scientific theses. In our view, scientific and theoretical reconstructions are not each other's generalizations, neither do they make up a continuous chain of conclusions. The theoretical position is not theoretical because it's a generalization of objectively verifiable theses in a normal scientific investigation, but because a thesis, as a semantic expression of a methodologically correctly fulfilled concrete real causal reconstruction, acquired the theoretical status in that concrete interpretation.

By reflecting on the possibility or impossibility of a theory of fascism, we must take the open paradox. From our methodological point of view, we must declare a theory impossible, of which object is one of the most well-known facts in our history.

The overlapping of the scientific and theoretical spheres revaluates in fact the classical science-philosophical relation of "facts" and "values" as well. It's not that the classical law of the value-free character of scientific theses gets attacked. Yet it becomes obvious that this separation ignores the peculiar fact that "scientific" (value-free) and "theoretical" (i.e. possessing internal and external values) measures get "copied" to one another at the reconstruction of real causality. Therefore it's not a coincidence that one of the most powerful representatives of this view, Heinrich Rickert was strongly against setting the reconstruction of a historical real causality as a goal of the theory of history, and pronounced his thesis that in fact seemed to be legitimated from his point of view, namely "Empirical history must not become a philosophy of history". But if we consider each research, which interprets fascism each with its own "real causality", and we know that every interpretation was founded on the same facts, it becomes clear that in the case of these rival options, the original separation of "empirical" and "philosophical" research loses more or less its meaning.

It's not a coincidence either, that the rigorous approach of facts and values that doesn't consider the reality of historical reflection can only accept historical laws (beside facts) like the "scientific explanation" of history, which puts "the development of positive sciences and technology" as "the real sense" of history. The reconstructed real causalities, one of which shall acquire a "theoretical position" and become a theory, relativize the fundamental thesis of the South-German neo-Kantian school, i.e. nature can only be interpreted in a "generalizing" manner, and history can only be interpreted in an "individualizing" manner. This thesis makes it clear that the "individualizing" method goes partly for the experience of a singular historical fact, and partly for the undefined "individual" character of each historical phenomenon. The above (on the example of fascism theories) represented phenomenon of "real causality as interpretation" can by no means be called "individualizing" in any sense, for interpretations (among others) don't necessarily use "individual" facts, nor strategies. Through the mere fact that a thesis, which articulates the results of a research for a real cause, has become an interpretation, makes that this phenomenon (real causality as interpretation) acquires some generalizing character, so we have to do with a generalization on an empirical basis, which founds a greater number of other generalizations.

But our analysis has not only established the fact that in fascism-theory, facts and values don't get separated by the classical science-methodological distinction, but also the fact that in this figure of "real causality as interpretation", values belong to the objective sphere, and the objective sphere also belongs to the sphere of values. In this case namely, not facts decide on values, but the value (as the integrator of a theory) shape the structure for the facts. It's true, a value in this position (shaping structures) is really a new function for values, we could say, in this position does a value become a fact of second order. This has also been justified in the concept of "real causality of interpretation". It gains special importance from the aspect that each reconstructed real causality that fights each other for the winner position, i.e. which makes it privileged in the form to be "theoretical".

The possibility of an existing One Theory of Fascism is by no means a task of normal science. Its further analysis can lead to a new, extended interpretation of the concept of "social fact", a new interpretation. It follows Émile Durkheim's concept in its logic, but in the point of getting its facts, it exceeds Durkheim's methodology.

Following from this, for example the statement "Fascism is totalitarianism" has three meanings. First, it's equivalent with a statement, which gives a normal-scientific explanation for the character of political order on the field of political science. Second, this statement also puts a systematic normal-scientific thesis, which puts its content in a reconstructive manner: "Fascism, as a social system, is totalitarianism". And finally, in its third meaning, the starting statement (evidently keeping its earlier normal-, scientifically systematic-, and reconstructive moments) becomes an "exclusive" theoretical thesis. The last is based already upon the reconstruction of real causality ("Fascism is totalitarianism, therefore it is not Bonapartism, not the dictatorship of the middle class", etc. "Fascism becomes fascism, because it was the most successful totalitarianism" i.e. in the concretization of the real cause as interpretation, we can identify the cause of the success of fascism).

The reconstruction of presentistic rationality

In the following, the term "rationality" is not meant as the rationality of "science" or science itself, nor as "science" in the generalized sense of philosophy or logic, or its methodology, but it is meant in its original, all-round sense, which grounds the whole of social and intellectual life. The fact that rationality and modernity are inseparable needs no further justification. As the modernization produced by the European way of progress, was practically equal with the increasing rationality of the different spheres of social life. This way of putting the Central European cultural acme as an independent variant of modernization defined by general rationality is in fact an attempt for pushing the limits of the typology of modern rationality pushing further. The term "modernization" and the "increase of rationality" are often not only synonimes, but are often considered equal.

The all-round explanation of the era of Vienna-style modernity with one concrete type of modern rationality is apparently easily challenged by the fact that modern culture in Vienna (and Central Europe) has created many unique and enduring pieces of art in a spirit that has made them "classical" pieces of modernity not by its "rationality", but right by its unique and pioneering "irrationality". We cannot completely solve this apparent contradiction now. We can just indicate the direction of the solution by assigning the great era of the Vienna (and Central European) culture to a direct and also indirect manifestation of this specific kind of rationality. The solution of this apparent dilemma is the fact that the victory of many seemingly completely "irrational" pieces of the Vienna-style modernity can be characterized as a reaction to the modern rationality that had just had its triumph before it. In fact, the victorious intellectual turn is unique because of its character. This can be proved by leading representatives of the "anti-rational" contents of modern Central European culture. For some, the modern, victorious rationality was too relativistic; for others, it was the opposite, too essentialist and theoretical (i.e. less existential); and for a third group, it was straight banal and empty, because of its all-round victory.

But it's not only this intellectual re-shaping of the intellectual status quo that took place at the triumphant breakthrough of rationalism, but a much more direct and straightforward process as well, which had hardly been taken into consideration so far. The victory of one particular type of rationalism can also change the situation. This is so inasmuch as even the most rational view or method might define for itself a new sphere of phenomena, which the intellectual public opinion had condemned as "irrational" so far. Rationality can also lead to the acceptance of new spheres of "irrationality".

This Nietzschean, Central-European type of rationality was intended to state a coherent concept of rationality, universally covering each field of the intellectual as well as the practical sphere. It devoted a lot of effort to its epistemological foundation, the distinction of the different elements of rationality in each intellectual group of phenomena, and the broadest possible extension of the sphere of rationality. Yet the recognition of the actual coherence of this type of rationality was seriously hindered by the fact that its anti-systematic character by which it rejected or relativized traditional theoretical systems, was often mistaken for a rejection of the claim for inner coherence, or straight the total lack of coherence.

The Nietzschean presentistic rationality possesses a unique decisionist trait as well. It was consciously aspiring for its wide spreading, and - what is more important - its utterly conscious enlightening mission, which suddenly established a direct connection between this type of rationality, and the overall phenomenon of the life-reform.

The Central-European type of rationality is originally of a pluralistic character. It respects the diversity of each objective sphere. It's sensitive to the extents to which each sphere of phenomena can be rationalized. This fact appears mostly in the tolerant and multitudinous statements of this particular rationality. The negative consequence of this pluralistic attitude is important as well: the lack of (quasi-) totalitarian tendencies. The organically pluralistic character of this type of rationality is based on the act of sticking to particular spheres of phenomena, and the acknowledgement of the relative ontological priority of spheres of phenomena in general.

One of the greatest achievements of the Central-European type of rationality is the ability to transform the particular phenomenal spheres into complexes; to find typologies and orders of classification, which make the elaboration of the phenomenal world on an increasing abstraction level possible. It does it without uniforming the particular characteristics of the particular phenomenal spheres at the same time. This ability of the transformation into complexes, and the science-theoretical issues connected with it, lead this kind of rationality to the elaboration of the term generally called the ideal type, or ideal typical character, after the terminology of Max Weber.

The maybe most important feature of presentistic rationality is the insight of the priority of the present. The great importance of this didn't only prevail in the fact that this rationality was in a great theoretical and methodological fight with German Historicism (which was but the great, direct debate of the two types of rationality), but also in the fact that the society and civilization of that time was defining itself through history to an extent almost unimaginable today. Thus the task of rationality was not to define the present in the flow of historical progress, but to directly interpret and categorize the present, and find descriptions capable of defining objectivities "here and now", without taking their positions in the historical flow into consideration.

From this rationality of science grew out the "science of rationality". The starting point in question was basically the same as the one Nietzsche grounded as critical empiricism elaborated in connection of historical identity and life reform, in a chapter of Human, All Too Human. The methodological leitmotif of this question was the completion of the evidence status of sciences that had played a key role for philosophy. Of course, Nietzsche is not the only emblematic figure of the shaping of presentistic rationality. Nietzsche was probably the only one of the prominent representatives of this rationality who lifted this turning point out of the narrow context of epistemology, and realized it on the fields of ethics, esthetics, and political philosophy. In this respect, Nietzsche compares with Kant, for he had also lifted the criticism of his age out of the narrow context of epistemology, thus making it a universal way of thinking.

To sum up: this presentistic type of rationality is a coherent concept of rationality, universally covering each field of the intellectual as well as the practical sphere. It devoted a lot of effort to its epistemological foundation, and the broadest possible extension of the sphere of rationality. Presentistic rationality originates from criticistic science. Presentistic rationality also possessed a unique decisionistic trait, which was of an enlightening character. It was consciously aspiring for its wide spreading, as well as putting its civilisatory and enlightening mission through; the wide spreading and generalization of a rationality of a naturally non-decisive and value-free basis. The presentistic type of rationality is of a pluralistic character. It respects the diversity of each objective sphere, and is sensitive to the diverse extents to which each objective sphere can be rationalized. The positive consequences of this fact appear mostly in the tolerant and multitudinous statements of this particular rationality. However, the negative consequences of this pluralistic attitude are more important. Another characteristic of this Central-European modernizing type of rationality is that it doesn't distinguish the rationality of cognition and that of understanding. The presentistic type of rationality is of a radically this-worldly character. Beside its positive this-worldly character, its immanent anti-methaphysical attitude is constantly reproducing its radical this-worldly character. Therefore it's metaphysical, still it's open to a positivistic way of theory-making. The presentistic type of rationality is reflective and self-reflective. It's aware of its interpretative-hermeneutical character, therefore it's open to coordinative structures as well.

Jegyzetek

1 Nietzsche's fundamental positivistic worldview may not be relativized by a quite great number of his explicit statements against sciences and methodological positivism in general. It is namely the key change between the second and the third period of the philosopher. For this reason, it's not an immanent question of a discoursive theory of truth, but simply a question of two great different historical and biographical periods. The statements of the third period are mostly motivated by a psychological dissolution and mental derangement of the thinker. From this issue, it can't really be a question that the concepts of the second period do represent Nietzsche correctly. It's another question, which values an interpreter wants to realize in the third period.

2 It also makes a surprisingly important comparison with the genuine Hegelian paradigm of the philosophy of history necessary. In other words, the genuine positivistic genealogy of the relation #1b and the genealogical interpretation of all topics by Hegel are not so far from each other. This idea can open the way to a seriously positivistic interpretation of the whole of Hegelian philosophy. It would mean that beside Nietzsche, the other "anti-positivistic" classic of the philosophy would prove to be a poor positivist.

3 A few years after writing this text, we can see there are a lot of PhD students who prepare their dissertations about topics of the history of climate.